Origins and Manifestations of Narcissism in the Life and Work of Walt Whitman

I hear and behold God in every object, yet I understand God not in the least,

Nor do I understand who there can be more wonderful than myself.

—Song of Myself

Thesis

Walt Whitman was a narcissist. His narcissism began in childhood when, as an infant unable to idealize his father or detach from his mother, he became his own love-object. Whitman’s attachment to his mother and disappointment in his father lasted throughout his lifetime and complicated his role in the Whitman family. His narcissism was the cause of both his obsession with the public’s reception of his work and his determination to be the nation’s poet. It is also the root of the autoeroticism in his poetry and an explanation of the fractured self his poetry portrays. Most poignantly, Whitman’s narcissism informed his homosexual impulses and the commingled pleasure and torture Whitman experienced as a nurse in the Civil War hospitals.

Research

In terms of theoretical research, I analyzed Whitman from a Freudian standpoint and did not address later theories of narcissism (either Lacanian or post-Freudian psychoanalysis) at length. Any information on post-Freud theories was based on Lynne Layton’s article, “From Oedipus to Narcissus: Literature and the Psychology of the Self,” which explores the roots of narcissism through a modern psychoanalytic lens. Primarily, I relied on theory provided by Freud’s essay “On Narcissism” in The Freud Reader, although I found useful information in some of his other essays as well (for example, Civilization and Its Discontents). “On Narcissism” was useful in defining narcissism and providing a theoretical framework with which to establish Whitman’s narcissism and relate it to his autoeroticism, homosexuality, and relationship with his mother.

Regarding historical research, I contextualized Whitman’s sexuality and mother-son relationship using Reynolds’s Whitman biography and Myrth Jimmie Killingsworth’s article “Whitman and Motherhood: A Historical View.” Reynolds provides an excellent description of the views of same-sex relationships in Whitman’s time and Killingsworth explains Whitman’s use of the motherhood mystique in relation to the intense mother-son relationships that were typical of the nineteenth century. My analysis of Walt Whitman’s narcissism was based on both biographical information and a selection of his writing that included the poems Song of Myself, “As at Thy Portals Also Death,” and “The Wound Dresser;” and the prose work Specimen Days.

Works Cited

Bauerlein, Mark. “Whitman’s Language of the Self.” American Imago 44.2 (1987): 129-148. Print.

Cavitch, David. My Soul and I: The Inner Life of Walt Whitman. Boston: Beacon Press, 1985. Print.

Fredrickson, Robert S. “Public Onanism: Whitman’s Song of Himself.” Modern Language Quarterly 46.2 (1985): 143-60. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. The Freud Reader. Ed. Peter Gay. New York: Norton, 1989. Print.

Killingsworth, Myrth Jimmie. “Whitman and Motherhood: A Historical View.” American Literature 54.1 (1982): 28-43. Print.

Layton, Lynne. “From Oedipus to Narcissus: Literature and the Psychology of Self.” Mosaic 18.1 (1985): 97-105. Print.

Moder, Donna. “Gender Bipolarity and the Metaphorical Dimensions of Creativity in Walt Whitman’s Poetry: A Psychobiographical Study.” Literature and Psychology 34.1 (1988): 34-52. Print.

Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage, 1996. Print.

Whitman, Walter. Walt Whitman: Poetry and Prose. Ed. Justin Kaplan. New York: Library of America, 1996. Print.

Zweig Paul. “The Wound Dresser.” Ed. Harold Bloom. Modern Critical Views: Walt Whitman. New York: Chelsea House, 1985. Print.

Donna Moder’s article, “Gender Bipolarity and the Metaphorical Dimensions of Creativity in Walt Whitman’s Poetry: A Psychobiographical Study,” really sparked my interest in Whitman’s relationship with his mother Louisa. In the article, Moder scrutinizes the interactions between mother and son and concludes that Whitman exhibited a “debilitating filial bondage to the widowed mother” (34). This bondage can be seen in their correspondence, which reveals Louisa as a “nagging, parasitic mother” who “frequently induced guilt feelings in Walt through her letters which followed him wherever he went, either hinting at the destitute family’s need for mortgage money, or bluntly requesting contributions” (Moder, 37). The ever-dutiful Walt regularly responded to these requests with the requisite financial support. Moder believes this is evidence that Walt “hungered for [Louisa’s] approval,” because he feared her love was not without its conditions (37). Whitman’s behavior after his mother’s death may also be indicative of an unhealthy mother-son bond. Moder explains that Louisa’s death caused Whitman to recede into a deep depression, during which time he lived in his mother’s room, slept in her bed, and spent the day “gazing at miniatures of her” (39).

But is it truly unusual for a son to seek his mother’s approval, try to assist her financially, and experience an overwhelming sense of loss at her death? According to Myrth Jimmie Killingsworth, it certainly was not unusual at the time. In his article “Whitman and Motherhood: A Historical View,” Killingsworth emphasizes the folly of holding Whitman to modern standards rather then viewing the mother-son relationship through its appropriate Victorian lens. When situated in its proper context, Whitman’s relationship with his mother is a reflection of “the culture from which he sprang,” which “encouraged a mystified and glorified mother-son bond” (Killingsworth, 39). In Whitman’s time, “the mother-son relationship took on an intensity bordering on the sexual in the novels of the day and in bereavement literature” (Killingsworth, 39). Though to modern readers it may seem that Whitman had an unnatural bond with his mother, “current information about nineteenth-century sentimentalism suggests that his treatment of motherhood was quite the norm” (Killingsworth, 40).

For my part, I have many more questions to consider before coming to a real conclusion on this issue. I suspect that the answer to the mama’s boy question will lie somewhere between the polar views of Moder and Killingsworth.

Works Cited

Killingsworth, Myrth Jimmie. “Whitman and Motherhood: A Historical View.” American Literature 54.1 (1982): 28-43. Print.

Moder, Donna. “Gender Bipolarity and the Metaphorical Dimensions of Creativity in Walt Whitman’s Poetry: A Psychobiographical Study.” Literature and Psychology 34.1 (1988): 34-52. Print.

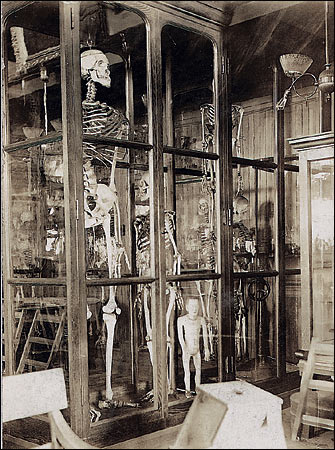

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia began collecting materials for a museum of pathological anatomy in 1849. In 1856, Dr. Thomas Dent Mutter, in poor health and intending to retire from teaching, offered the museum the contents of his personal collection of “bones, wet specimens, plaster casts, wax and papier-mâché models, dried preparations, and medical illustrations.” In addition, Dr. Mutter offered the College of Physicians a $30,000 endowment to pay for the administrative costs of running a museum. Dr. Mutter’s collection was added to the materials collected by the college since 1849 and the Mutter medical museum was born.

Mutter’s endowment facilitated the purchase of additional collections in Europe, and as students from the college “contributed interesting surgical and post-mortem specimens acquired from their hospital and private practice,” the museum’s collection grew. The College decided in 1871 to start collecting old-fashioned medical tools in an effort to document the “changes in the technology of medicine and memorabilia of present and past practitioners.” The majority of the museum’s contemporary acquisitions are of this type.

As the museum’s holdings continued to increase, a larger building was required. Construction began on a new space in 1908. Although the building itself boasted elegant marble and carved oak details, the medical exhibits still resembled “the utilitarian medical museums typical of 18th century hospitals and medical schools,” which “illustrated the fact that the museum’s purpose lay not in the decorative display of selected artifacts, but in the organized assemblage of teaching materials which were to be available to the student or researcher as were books on a library shelf.” In 1986, a major renovation of the museum’s exhibit areas modernized the shelving and lighting, presumably altering the nostalgic atmosphere.

Although I am unsure whether or not Walt Whitman visited the Mutter Museum, I am interested in exploring Whitman’s views and experiences with medicine. In particular, I am interested in the time Whitman spent nursing wounded soldiers during the Civil War. According to Reynolds, Whitman saw himself as a healer, and he had a severe distrust of medical doctors. Nursing the soldiers “intensified his distaste for conventional medicine and permitted him to test out his homespun ideas about healing” (430). The war doctors were overwhelmed with injured soldiers, and they were forced to perform surgeries with inadequate equipment and ineffective painkillers. This was a time when “medicine was still primitive,” and though Whitman “sympathized with the overworked war doctors, he recognized their limitations and believed that his own magnetic powers were as effective as all their procedures” (431). Many of Whitman’s “homespun ideas” were based on building interpersonal relationships with the soldiers. Whitman devoted a considerable amount of time to talking to the soldiers, reading to the soldiers, and helping them to write letters. Reynolds notes that: “to the end of his life Whitman would look upon regular doctors and their drugs with suspicion” (332).

According to its website, the Mutter Museum has “specimens and photographs of battle injuries” from the Civil War within its collection. These artifacts were acquired from the Army Medical Museum “in exchange for duplicate material from the Mutter to be used for the training of army surgeons.” If Whitman were to visit the Mutter, I would venture to guess that this exhibit would be of special interest to him.

Please click on the link below to see some of the Mutter Museum’s current holdings. These photos are not for the faint of heart!

http://www.flickr.com/photos/42620318@N06/galleries/72157622808660274/

Works Cited:

History of the Mutter Medical Museum adapted from:

http://www.collphyphil.org/erics/Mutthist.htm

Information on Walt Whitman’s views on medicine taken from:

Reynolds, David. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage, 1995. Print.

Lead Image provided by:

http://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/2005/10/10/arts/11mutt-slide1.jpg

For the bibliographic essay assignment, I researched recent psychoanalytic criticism of Walt Whitman and his work. Please click on the link below if you are interested in learning more.

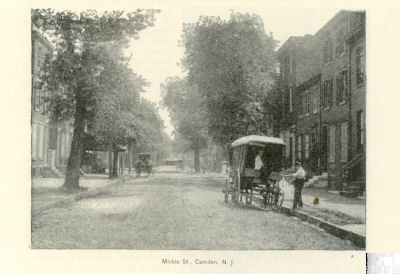

According to the Reynolds biography, Whitman enjoyed living in Camden, which in the late 1800s bore many similarities to his native Brooklyn. Reynolds describes it as “a small but fast-growing industrial city linked by ferries to a major city across a beautiful river” (510). Whitman enjoyed the sounds of the city’s industry, particularly those of the factories, mills, and trains (510-511).

There was a “rural feel” to Whitman’s neighborhood, and it seems to me that Whitman would have experienced—and enjoyed—a true sense of community (554). Whitman’s house is described by Reynolds as something of a hovel, but the neighborhood was lively. Reynolds describes Whitman as “a distinctive sight in the neighborhood” (550) and says that children waited beneath Whitman’s window for “the pennies he sometimes tossed down” (549). They also had “a playful terror of his house, into which, they pretended, people entered, never to be seen again” (549). The lively neighborhood was filled with the sights and sounds of trains, children, street vendors, and the whistles of nearby factory and ships (549-550).

For Whitman, there were some negative aspects to life in the Mickle Street house. These annoyances include some local sounds that Whitman did not appreciate—a practicing choir at a nearby Methodist church, the “traveling bands that roamed Camden in bad weather,” and the barking of Mrs. Davis’s dog (550). The odor of a fertilizer factory across the river and the repressing heat and humidity of the summers were also less than ideal. Reynolds tells us even with these detractions, Whitman “still…didn’t think badly of Camden” (550).

Whitman lived in Camden for almost twenty years—from 1873 until his death in 1892. Before his death, he chose Camden as his final resting place and the site of the family tomb he constructed. Whitman chose to be buried in Camden’s Harleigh Cemetery “because of its association with his recent family life and its bucolic layout” (571).

Last week when we walked from campus to Mickle Street for our class tour of the Whitman house, I found myself wondering if Whitman would enjoy modern day Camden. Reynolds writes, “today, when Camden is a ghost of its former vibrant self, the Mickle Street Area is virtually noiseless, a place where urban blight seems to get the best of urban renewal. In Whitman’s time it was alive with sound” (549). Camden is certainly not the bustling hub of industry that it was in Whitman’s time. There is very little life or sound on Mickle Street, and the neighborhood seemed neglected and uninviting. The vibrant description of nineteenth century Mickle Street provided by Reynolds stands in stark contrast to today’s Mickle Street. Observing this contrast has increased my interest in the social and economic factors that affected these changes in Camden since Whitman’s time.

Reynolds, David. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage, 1995. Print.

Having recently identified psychobiography and psychoanalytic criticism of Whitman’s work as potential topics for a bibliographic essay, I was especially interested in the portions of Betsy Erkkila’s Whitman the Political Poet that provided insight into these areas. In terms of psychobiography, Erkkila reveals that “immediately after the war, Whitman appears to have suffered from a kind of shell shock that manifested itself in physical symptoms and psychic stress” (279). I am interested in first identifying the textbook symptoms of shell shock and then determining exactly with which of these physical and psychic symptoms Whitman may have been afflicted. I am also intrigued by Erkkila’s statement that “although he may not literally have inhaled poisons in the war hospitals, as he sometimes claimed, his stroke was at least partly a result of the psychic demons that came to haunt him during and after the war years” (279). I am intrigued that Whitman believed himself, whether literally or figuratively, to be poisoned by his experience of nursing soldiers in the war hospitals, and I find myself wondering if this was a topic that he addressed or alluded to in any of his later poems.

Psychoanalytic criticism can be practiced from a variety of perspectives, but it is my understanding that the critic must first have a solid understanding of its Freudian roots. Regarding existing Whitman criticism Erkkila states, “Freudian critics have taught us to see beneath the mask of the bard of democracy the anguished visage of an American neurotic, but they have read Whitman’s neurosis as a merely personal affair. I am interested in the ways that Whitman’s family romance was bound up with the romance of America—in the ways the signs of personal neurosis and crisis we find in his poem are linked with disruptions and dislocations in the political economy” (11). From reading the Reynolds biography, I have learned that Whitman hoped to be “a poet that could tyrannically survey the entire cultural landscape and give expression to the full range of voices America had to offer,” and that he believed “poetry might just help restore the togetherness that politics and society has destroyed” (308-309). For my purposes then, it would be useful to consider psychoanalytic criticism of Whitman’s work from both perspectives— that of the poet’s private neuroses as well as his representation of broader social and political crises.

I am particularly drawn to psychoanalytic criticism focused on myth and the collective unconscious. In terms of Whitman and myth-making, Erkkila claims “there was a need for a new myth, a myth of community and control, to counter the runaway force of laissez-faire individualism. Rather than proposing more government authority, Whitman encouraged an ethos of social responsibility by evoking a mythos of national union, a religiomystical and essentially matriarchal vision of the Union as a political ordering bound not by law or imposition from above but spiritually by a sense of common values and shared traditions” (278). Exploring if and how Whitman’s role as a myth-maker relates to mythic criticism is certainly another potential angle to consider in my research. Additionally, Erkkila contends that “Whitman was working toward a wholly new concept of artistic expression, an art originating not in the particularities of individual experience but in the collective consciousness of the masses, in which nobody speaks or holds the stage alone” (278). From this perspective, it may be useful to contrast Whitman’s view of the collective consciousness with a psychoanalytic view of the collective unconscious.

In addition to providing all of these interesting avenues of potential investigation, Erkkila’s notes list some possible sources for early “psychosexual explanations of Whitman’s poetic origins” (324). Although these sources, ranging from 1955-1985, are not as contemporary as those I plan to use during my research, it may be worth looking at a few of them to get a sense of the development of this topic over a thirty-year period, as well as a grasp of traditional psychoanalytic methodologies.

Erkkila, Betsy. Whitman the Political Poet. New York: Oxford UP, 1989.

Reynolds, David. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage, 1995.

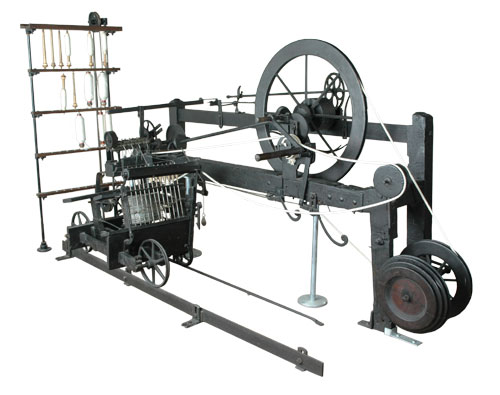

The spinning-girl retreats and advances to the hum of the big wheel (pg 39)

The OED defines a wheel as a circular frame or disc arranged to revolve on an axle and used to facilitate the motion of a vehicle or for various mechanical purposes. When reading Whitman’s line, I am thinking of the wheel in the context of the Industrial Revolution, which was ongoing from Whitman’s childhood through several editions of Leaves of Grass.

The Industrial Revolution affected most areas of nineteenth-century American life, and the wheel was an integral part of many innovations. Wheels were an essential component in most modes of transportation at a time when the railroad was expanding and the first automobiles were beginning to appear. In the textile industry, wheels were used as gears on spinning mules and looms.

Wheels were also used in steam engines to power factories and mills as well as the machines inside of them.

Follow this link to see a steam engine at work:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Steam_engine_in_action.gif

According to Reynolds, Whitman composed several “technology poems” and poems about the machine age (521). This line from Song of Myself is bookended by:

The deacons are ordained with crossed hands at the altar

and

The farmer stops by the bars of a Sunday and looks at the oats and rye

The fact that the spinning girl and her wheel are placed in a series of images of everyday people in their typical occupations is an acknowledgement of industry’s rightful and fundamental place in Whitman’s culture and poetry.

Song of Christina

Swift wind! Space! My Soul! Now I know it is true what I

guessed at;

What I guessed when I loafed on the grass,

What I guessed while I lay alone on my bed… and again as

I walked the beach under the paling stars of the

morning.

For me, these lines represent those beautiful but fleeting moments of my life when I’ve been completely engulfed by clarity and peace. These are moments of solitude and meditation—sitting by the ocean, strolling through a gallery, wandering through a garden—during which I suddenly realized the answers to the big questions were within reach, and all was, and always had been, right with the world. They are the moments that forced me to slow down, acknowledge the magnificence of my surroundings, and embrace, however temporarily, a rejuvenated and fearless perspective.